As a community-based Speech Pathologist, one of the most frequent questions I get is, “What is Autism and what does it mean for my child?”

This is often followed up with, “How do we treat it?”

To answer these questions in full, we need to go back to what it means to be neurodivergent.

Neurodivergence is a general term for when a person’s brain processes and learns things differently, or they behave in a way that is different to what is considered “typical”. For example, an Autistic individual might react differently to sensory stimulation or may communicate best using alternative methods.

This is because their brain is hardwired differently.

Neurodivergence can include a range of people diagnosed with:

- Autism

- ADHD

- Dyslexia

- Dyscalculia

- Stuttering

- Dyspraxia

- Aphasia

- Synaesthesia

- Genetic conditions such as Down Syndrome or Fragile X Syndrome

- Chronic mental health conditions such as bipolar disorder

- And many more

ID: A Speech Pathologist with an elderly woman both saying the word apple.

When I first read the definition of neurodivergence as I was studying to be a speech pathologist, I remember feeling incredibly confused as to why we needed a definition when we clearly had specific diagnoses already. However, as I gained experience and grew as a clinician, I began to understand the true concept of neurodiversity and why it is so important for the community.

Firstly, let’s think about some scenarios that many people who are neurotypical may encounter.

- Have you ever spoken with an Autistic person and noticed that they were reciting lines from a tv show they have watched?

- Taught someone with ADHD and wondered why they can’t “sit still” and “focus” on what you’re saying?

These are both scenarios I have come across in my day-to-day life, and whilst the setting and scene may be different, I know many others who have encountered similar situations.

What if I told you that for an Autistic person, repeating lines (also known as delayed echolalia) is actually a useful language learning process, and a way they can express themselves. Or that an individual with ADHD actually learns better when they are free to move around. In either of these cases, there is no harm being done, and if you understand the different ways that brains can work, you will be able to improve how you communicate with neurodivergent people.

Although this may be a relatively simplistic perspective of the true range of neurodiversity, in both of the above scenarios, people judge someone who is neurodivergent based on behaviours expected by a neurotypical society and becoming frustrated when they don’t conform.

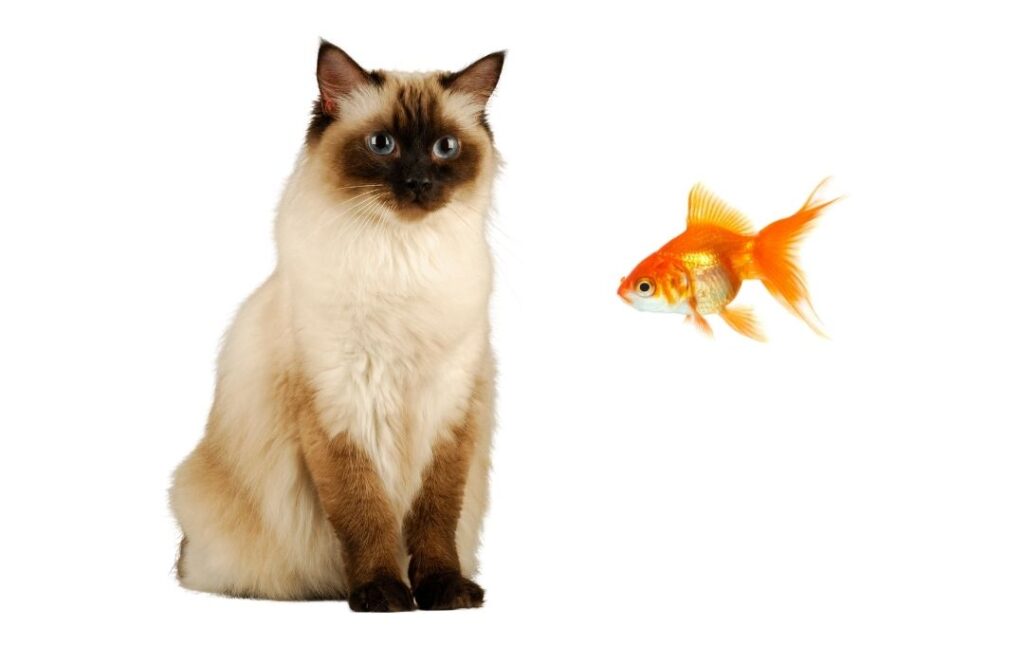

The Cat & Fish Experiment

Think of a science experiment comparing how well a cat and a fish adapt to living inside a fish tank and getting frustrated that a cat doesn’t do very well.

Yes, they are both animals; however, their overall anatomy is very different and only one of these animals is suited to living in the fish tank environment.

Similarly, neurotypical individuals are better suited to living in a society based on neurotypical norms. We’re essentially asking someone with a different brain structure to adapt to a neurotypical way of being and setting them up to fail.

As humans, we tend to pick out differences as being bad or as something to “fix”, but if it isn’t hurting anyone, is it really a problem? Neurodiversity should instead be taken as an opportunity to recognise how diverse the human population really is.

When I work with any individual who is neurodivergent, I am never focused on “fixing” them or showing them how to do things the “typical” way. This approach can often encourage masking, which is when the individual spends all their focus just trying to fit in and act “normal”. This is to the detriment of everything else and can be very stressful long term.

Instead, I try to embrace neurodiversity as part of one’s identity and focus my attention on working with their strengths and changing the environment to better support the individual. For example:

- Building on an individual’s use of echolalia (repeating lines) until they can functionally use this as a means of communication.

- Or introducing a communication device which allows an individual to interact and communicate through means other than speech.

This helps to ensure the individual has access to a reliable means of communication for when they need it and can advocate for themselves.

So, to go back and answer our original question of “how do we treat it?”, the simple answer is “we don’t.”

Signed

Gabi Chatwood

Speech Pathologist